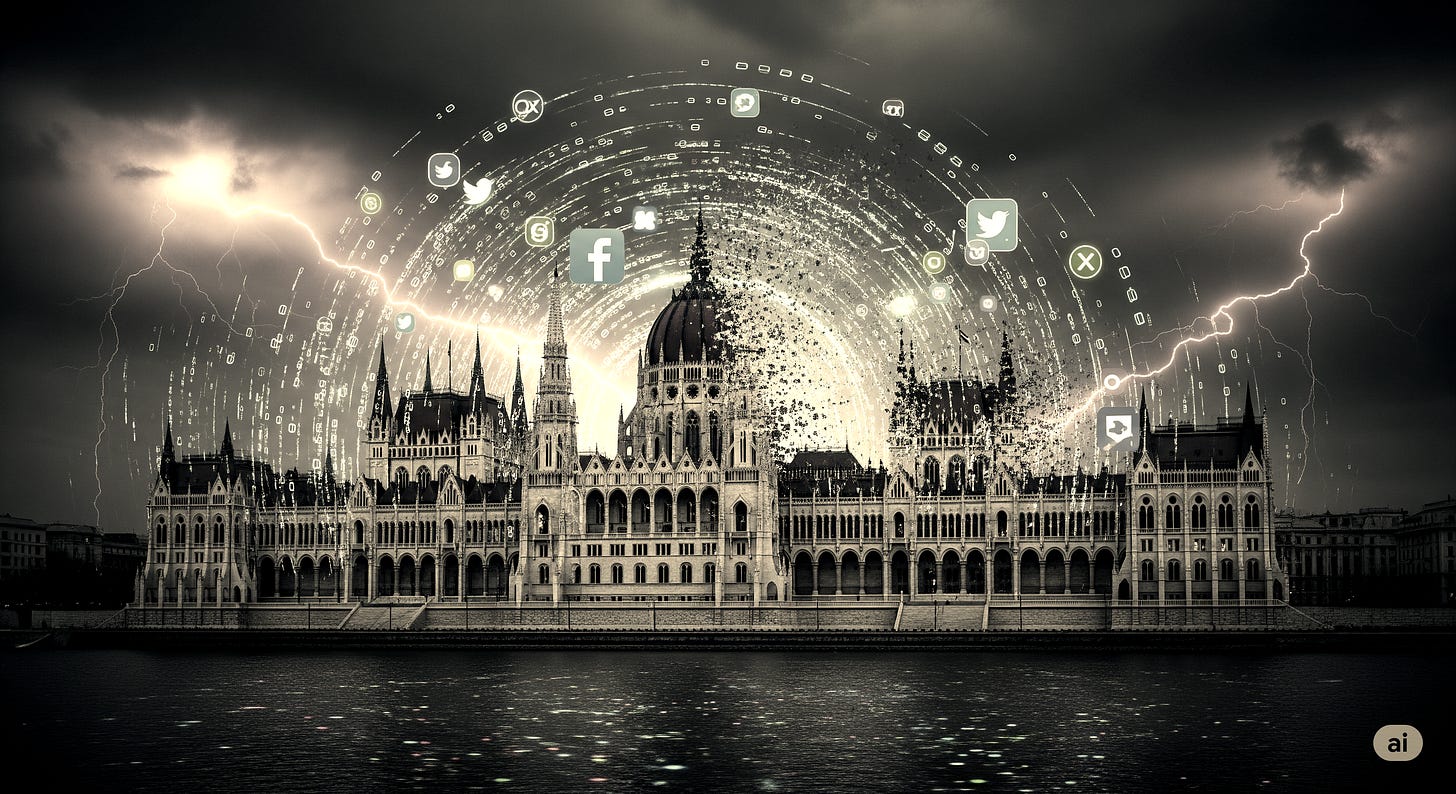

Cybersecurity Challenges of the 2026 Hungarian Parliamentary Elections

Risk Analysis and Information Warfare Scenarios

TL;DR

The information environment of the 2026 Hungarian parliamentary elections is expected to be defined by four main risk factors:

The synergy of domestic government and foreign (primarily Russian, American, and Chinese) disinformation, creating a coordinated, mutually reinforcing narrative space.

Networked propaganda that bypasses the ban on paid politi…